Discover more from A Campus Resident

UBC’s Point Grey campus is situated within a forest surrounded by parks and beaches. It is also accessible by the remnants of three double lane highways: Chancellor Boulevard on the north, 16th Avenue entering mid-campus from the east, and SW Marine Drive from the south. These roads date to the period of highwayification of the 1960s and 1970s. At one point Wreck Beach, on UBC’s extreme west, was the proposed site of a major BC Ferries terminal (this idea persisted well into the 1980s). All this makes the UBC area a great place to walk and a potentially dangerous place to walk.

My partner and I spend most early mornings walking around campus. Some mornings we just head down Main Mall and back, other days we walk toward the Botanical Gardens and north along Marine Drive. Or we might trek down old Marine Drive to watch the tugboats working the log booms. We even occasionally take longer walks to Spanish Banks or into the heart of Pacific Spirit Park. Each of these routes have particular spots of beauty but also hazards.

A few weeks ago, as we walked by the new safety equipment on Marine Drive, we wondered about the problems with overlapping authority and jurisdiction on these campus perimeter roads. The new sign flashed orange numbers: 60, 45, 67, 38 … as cars sped toward the curvy portion of Marine Drive. We paused a moment and wondered about changing the road alignment or maybe adding speed bumps or something here.

It’s not just that location, try crossing Marine Drive a bit to the south, from Stadium Road over to the UBC Botanical Gardens. That’s often a heart in your throat, jog fast across the road, as drivers appear oblivious to us (even when we are decked out in lights and high visibility coats). These are only a couple of the places that feel a bit on the dodgy side of safe.

Who’s in Charge?

Jurisdictionally the roads outside the campus core are under the authority of the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure (MoTI). For the policy trivia buffs, UBC has provincial authority to issue tickets on the academic roads for parking and traffic violations. The roads in the UNA areas, despite have a UNA policy in place, are formally under the authority of the Ministry. Thus parking regulations are worked about between UBC, MoTi, and the UNA and, for reasons I will skip, result in the ‘tow, no ticket’ rule in the UNA for parking violators. All traffic regulations on the MoTI roads are set by MoTI in accord with the motor vehicles act. Since UBC is technically ‘private’ land, UBC sets the rules for campus core roads. Enforcement generally falls to UBC for the campus roads. The RCMP is responsible for enforcing all traffic regulations on MoTI governed roads.

I wanted to get a first hand explanation from those responsible for road safety and how they ensure it gets done. So I sent an email to a District Manager with responsibility for MoTI roads at UBC. They had nothing to say to me. Directly.1 I’d all but given up. Then I got an email from a journalist who once interviewed me about my academic research in Gitxaała (he then worked for CFNR out of Terrace, BC). Today he works out of Victoria in the provincial government’s communications and community engagement office. We had a pleasant series of emails. After a period of time he managed to get me an official statement:

Improving safety for people who choose cycling and other types of active transportation is a commitment of the government. The roads around the perimeter of UBC's Vancouver campus are mainly provincial public highways (except for private roads under direct ownership and management of UBC). While all provincial public highways are administered by the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, the roads surrounding the perimeter of UBC’s Vancouver campus are managed by UBC, University Neighbourhoods Association (UNA), University Endowment Lands (UEL), or MOTI (depending on location). The ministry works closely with UBC and the UNA to manage provincial infrastructure for the safety of all users. Local residents are encouraged to speak with UBC/UNA for further information on jurisdiction or any issues or concerns that can be brought forward to the ministry if required.

It is nice to learn that the entire government of BC is committed to improving my safety as I walk and cycle around campus.

I had better luck with UBC Campus and Community Planning. They scheduled a sit down meeting with me. So on October 4, 2022, I meet with Michael White, Associate VP Planning and Krista Falkner, Manager, Transportation and Engineering.

Michael, Krista and I had a wide ranging conversation - too big to include completely here (a more focussed story on our conversation will follow next week). The key lessons I took from this are: the overlapping jurisdiction are an issue, but UBC & MoTI do try and make things work; UBC’s priorities on the perimeter roads don’t necessarily mesh with the regulatory and traffic flows envisioned by MoTI (but they try to work it out), and; things are changing with more attention to ‘multi-model transportation’ along the perimeter routes.

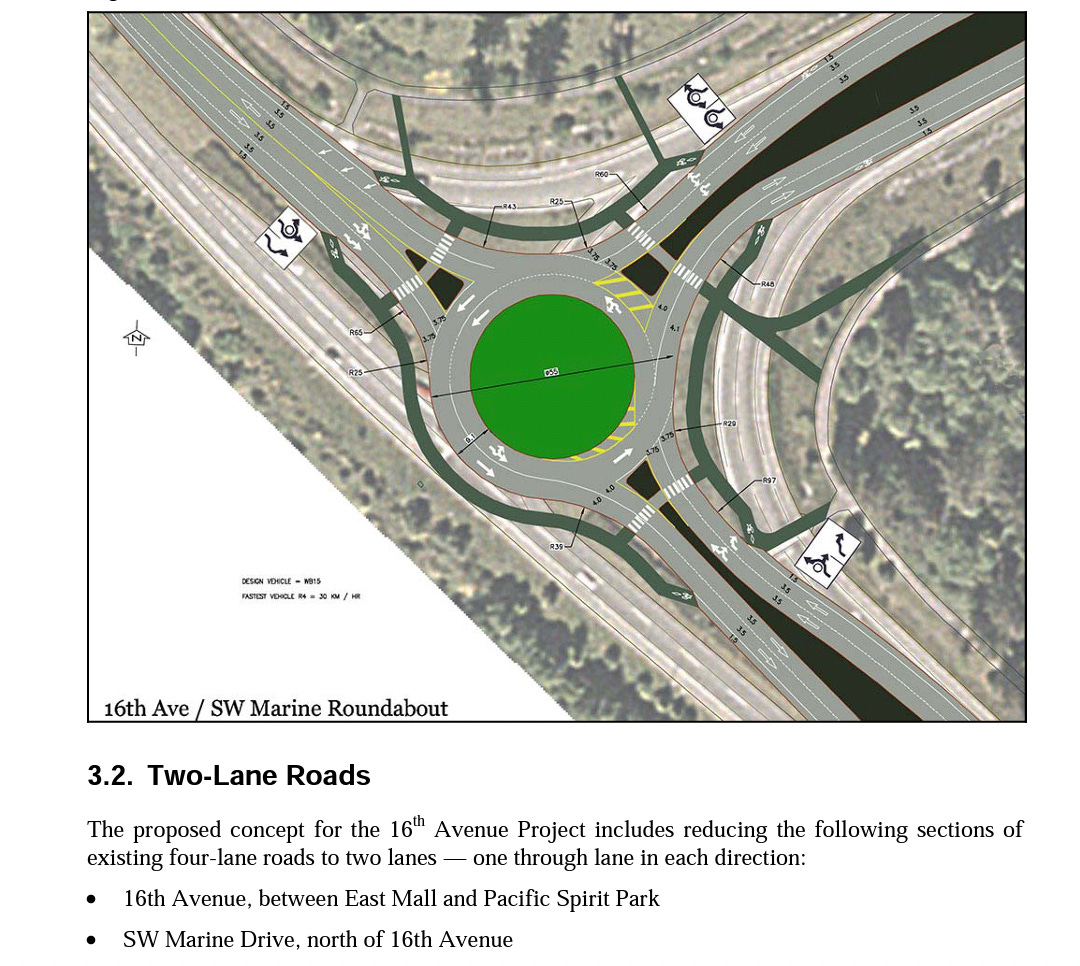

A lot of the things UBC has done does make things safer. Krista noted UBC intersections, for example, “have low rates of collision compared to our neighbours. [The accident data] doesn't generate any concern. … In terms of ranking our intersections with our neighbours’ [intersections]. we're nowhere near them. Changing standard intersections into roundabouts on 16th Avenue was an important safety change that made a difference.2

Michael pointed out an important conceptual distinction: the difference between “planning with intention” and “planning in response.” A lot of what we see as outsiders to the planning process is planning in response: safety modifications put in place after community lobbying or in response to an observed traffic problem. The hidden work of planing with intention isn’t often noticed becuase it’s happening over the long term and often behind closed doors. Much of what planners are doing is in the second category, what we usually see is in the first.

Common Safety Controls

Traffic managers have a range of techniques to ensure pedestrian safety. Such techniques range from road design, to passive interventions (feedback signs or props in or on the road), to direct enforcement of bylaws. Here I describe common techniques, examples of which can be found around UBC’s campus.

Pedestrian Islands: “The use of traffic islands and raised medians is an excellent practice especially on multi-lane roadways where the roadway is too wide for most pedestrians to cross safely. The median breaks up the crossing into smaller more manageable distances” (Countermeasures to improve pedestrian safety in Canada, 2013). There are several such installations on campus perimeter roads. Two on NW Marine Drive (Near AnSo Building and Green College) have been in place for close to a couple of decades. They were installed after series of road accidents provoked a community lobbying effort.

Radar Speed Feedback Signs: Also called Dynamic Speed Monitoring Display sign, this tool has become increasingly popular with traffic engineers in North America over the last decade. UBC has two permanent installations: one on East Mall at Eagles Drive, the other where SW Marine drive transitions from a straight double lane highway to to single lane residential road with a sharp ‘s’-curve.

The research on feedback signs show they do reduce average speeds in a statistically significant fashion, but in absolute terms only between 1 to 5km/hr. The research indicates that these feedback signs work best at speed transition zones around schools or parks and along streets with roadside parking.

Passive Props: Some years ago I used to live along West Mall at Hawthorn Lane. At that time the 41st bus route went along West Mall, to Totem Park Residence, and then up Thunderbird to the center of campus. The road configuration of Marine Drive and Stadium road (that feeds into West Mall) was quite different then, and facilitated high vehicle speeds up West Mall. One neighbour found a technique that helped slow traffic - they placed an over turned tricycle in the center of West Mall near our homes. It worked like a charm until someone else removed it.

Campus RCMP have been using cut outs of enforcement officers in the same way my neighbour once used an upturned tricycle.

All of these passive measures appear to have momentary effects that contribute to pedestrian safety. However, once the prop is removed or drivers learn it is simply a prop, the effect dissipates.

Police Enforcement: Saturation enforcement (concentrating several offices at one place for s short period of time) seems to work the best at controlling speed infractions and reducing accidents. Rylan Simpson (SFU Criminology) conducted a study with two RCMP officers on the effects of saturation enforcement on a lowermainland highway. This is an expensive operation however, and rarely have I noted UBC’s RCMP detachment engage in saturation enforcement on campus. However, Vancouver Police Dept has periodically set up speed traps leaving campus on Marine Drive at 41st Avenue and on 16th east of Blanca.

That about covers the main interventions to manage car/pedestrian interactions on UBC’s perimeter roads. There are other techniques embedded in the overall planning process: road sides, surface treatments, signage, raised and separated bike paths, etc. One of the best safety approaches comes down to being a defensive walker, wearing bright clothes with lights, being careful and vigilant. I don’t like prioritizing individualistic solutions over structural changes (they are ultimately less effective), but even if I’m in the right a car will win if I get in the way.

When Changes Happen

A lot of the road safety modifications seem reactive, rather than proactive. Or, to use the words of Michael White, “planning in response, versus planning with intention.” The general public typically only sees the planning in response. This is partly because so much of what takes place between MoTI and UBC happens removed from public view. Michael wants there to be more transparency in the process (hence his and Krista’s willingness to meet with me to talk about pedestrian safety). MoTI was only able to offer a short statement from their provincial communications officer. Especially as we ramp up on Campus 2050 MoTI will need to become more publicly present given their control over most of the campus perimeter roads.

That we mostly see changes made in response is also party because there are moments when public scrutiny does drive reactions from the authorities. In the 1990s the light at 16th and Blanca was put in place after a serious bicycle accident. The pedestrian island on NW Marine Drive by Green College and the AnSo Building came following a public campaign after several pedestrian injuries in the crosswalks there. The pedestrian controlled crosswalk at Eagles Drive and East Mall came following major community lobbying following a series of pedestrian injuries and car crashes. Clearly safety is a driving concern, but it is one always mitigated by the cost of safety measures. Devices that appear to work (like radar speed feedback signs) and don’t cost as much as direct enforcement are the solutions managers appear to favour.

UBC has invested heavily in shifting students and employees out of cars and into public transit (while maintaining private car trips at just below 1997 levels). Currently UBC is strongly advocating for the extension of skytrain all the way to campus (and has suggested the university will contribute funds to help make it happen). Yet we still have three double lane highways feeding into campus. It might be time to downsize the feeder highways to single lane. In 2006 UBC had suggested turning 16th between Wesbrook and Marine Drive and SW Marine Dr from 16th northward into single lane each way - but that never happened.

As UBC explores its future in Campus 2050 rethinking the highways feeding into campus may well end up front and center in community reflections.

Updated Oct. 5, 2022 to delete the name of the district manager. After story was published one of the communication staff called me up to explain the district manager had not ‘ghosted me,’ but following their provincial policy sent my request to the Communications and Community Engagement office to process. I shared with the comms staffer that “I appreciated their perspective that the district manager had not ignored me and that I understood their concern that their intention to reply had not been fully understood by me.” I also offered that it might be a nice idea to have acknowledged receipt of my email at the time it was received and to have advised it would be dealt with according to provincial policy for government workers.

When the roundabouts were first introduced a lot of people were upset and thought they were more dangerous, not safer. The evidence then and today is clear, roundabouts are much safer that standard intersections.

Subscribe to A Campus Resident

news and commentary on things that happen in the life of a university prof who also lives on campus.

excellent piece, Charles. As a pedestrian, I found it very insightful.

Great piece Charles! Walking my kids to school across both East Mall and Wesbrook we often experience drivers going right through the crosswalks while the crossing lights are blinking and have never seen any RCMP out to enforce this, although I know that they are busy with a variety of issues on campus.

One other question around traffic safety is if you have noticed what I assume are traffic cameras that have been setup around campus (I've noticed these at Thunderbird and Wesbrook, Thunderbird and East Mall, and 16th and East Mall). In your conversations have you had any discussion about these, what their purpose is, and who is monitoring/collecting data from them?